I have summarized the international evidence in earlier research (Rogoff 1998, 2002). And yet there is a significant body of evidence that a large percentage of currency in most countries, generally well over 50%, is used precisely to hide transactions. (A slight caveat is that the identity of the buyer might be correlated with the probability of the currency being counterfeit, but until now this is a problem that governments have been able to contain.) There is nothing, however, in standard theories of money that requires transactions to be anonymous from tax-or law-enforcement authorities. Standard monetary theory (e.g., Kiyotaki and Wright 1989) suggests that an essential property of money is that neither buyer nor seller requires knowledge of its history, giving it a certain form of anonymity. (The issue of substitute anonymous transactions vehicles, such as Bitcoin, is discussed later on.) This is a big difference from most forms of electronic money that, in principle, can be traced by the government. Paper currency facilitates making transactions anonymous, helping conceal activities from the government in a way that might help agents avoid laws, regulations, and taxes. We now turn to a second drawback to paper currency. If, as Reinhart and Rogoff ( 2014) conjecture, business and financial cycles in the twenty-first century may produce larger fluctuations than they did in the last part of the twentieth century, the issue of hitting the zero bound may indeed remain a recurrent one.Īnonymous Money as a Vehicle for Facilitating Tax Evasion and Illegal Activity Nevertheless, the challenges of conducting monetary policy at the zero bound force consideration of alternatives to the status quo. Robert Hall ( 1983) argues forcefully that the central role of monetary policy should be to provide a stable unit of account, and in principle the ability to pay negative interest rates facilitates its ability to achieve this in today’s low inflation environment (Hall 2002, 2013).Įven if there is a good case for allowing the central bank to pay a significant negative interest rate to fight a large deflationary shock, what is to stop a government from using negative interest rates as a wealth tax in normal times? This is a complex issue that parallels many of the problems in trying to design central bank institutions that will resist the temptation to inflate. Arguably, paying negative interest rates is a better approach if, as many believe, inflation becomes more unstable as the general level of inflation rises. point out that if central banks permanently raised their target inflation rates from 2% to 4%, it would leave them scope to make deeper cuts to real interest rates in severe downturns. The idea of raising target inflation to reduce the likelihood of hitting the zero bound is indeed an alternative approach. Paying a negative interest rate on currency, or on electronic reserves at the central bank, may seem barbaric to some, but it is arguably no more barbaric than inflation, which similarly reduces the real purchasing power of currency.

#Coins are more valuable than notea serial#

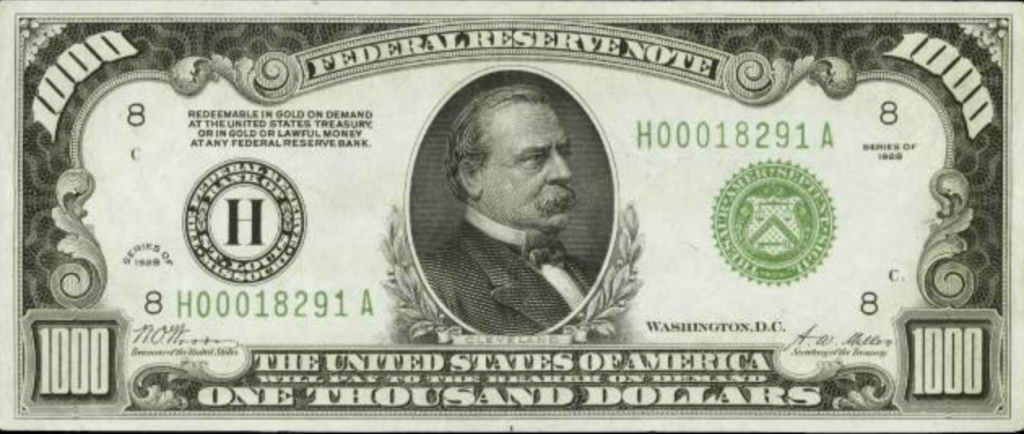

For example, Mankiw ( 2009) points out that the central bank could effectively tax currency by holding lotteries based on serial numbers, and making the “winners” worthless.

3 Buiter notes that there were experiments with stamp taxes during the Great Depression (currency would remain valid only if it were regularly stamped to reflect tax payment).

#Coins are more valuable than notea series#

In a series of insightful papers, Willem Buiter (, and citations therein) has discussed whether it might be possible to find devices for paying negative interest rates on currency.

Hoarding cash may be inconvenient and risky, but if rates become too negative, it becomes worth it. But as long as central banks stand ready to convert electronic deposits to zero-interest paper currency in unlimited amounts, it suddenly becomes very hard to push interest rates below levels of, say, −0.25 to −0.50%, certainly not on a sustained basis. If all central bank liabilities were electronic, paying a negative interest on reserves (basically charging a fee) would be trivial. The low overall level, combined with the zero bound, means that central banks cannot cut interest rates nearly as much as they might like in response to large deflationary shocks. As Blanchard, Dell’Ariccia, and Mauro ( 2010) point out, today’s environment of low and stable inflation rates has drastically pushed down the general level of interest rates. First, it is precisely the existence of paper currency that makes it difficult for central banks to take policy interest rates much below zero, a limitation that seems to have become increasingly relevant during this century. Paper currency has two very distinct properties that should draw our attention. Zero-Interest Negotiable Bonds as an Obstacle to Negative Policy Interest Rates

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)